Stories

Mapping Taos’ Cultural Assets to Protect the Past and Guide the FutureAmid booming growth, a Taos County initiative charts a path toward sustainable development and community preservation. Read more

Volunteers with Taos' Shared Table Food Pantry load a car with boxes on Dec. 23, 2025. The food will be transported by family, friends, and community members to residents who can't visit the pantry on its biweekly distribution day. Photo by Ryan Michelle Scavo

New Mexico is known for many foods—red and green chiles, calabacitas, biscochitos. But pineapples certainly aren’t one of them. So when an elderly resident in Questa, a small village of some 1,800 in northern New Mexico, received 15 pineapples from the local North Central Food Pantry, she wasn’t sure what to do with them. Thankfully, she had a friend in Rosie Turpin, a local restaurant owner with a knack for whipping up meals—and preserving food—from all kinds of ingredients. Turpin helped her can the pineapples, creating a shelf-stable supply that lasted the woman for a year.

The experience sparked an idea for Turpin. “Our food pantry here is phenomenal when it comes to fruits and vegetables,” Turpin says. “But if I give you 30 pounds of grapes, what are you going to do with it if you don’t know how to preserve it?” She knew that with the right supplies, she could teach Questa residents how to make healthy meals and preserve the food they received from the local food bank, helping to stretch their ingredients—and fill their bellies—even more. So she reached out to the LOR Foundation for funding to help her get her classes off the ground.

With a grant from LOR, Rosie Turpin, the owner of Rosie’s Smokehouse in Questa, New Mexico, launched a series of cooking workshops aimed at helping Questa families who don’t know how to prepare or preserve the foods they receive from the local food pantry. Photo by Ryan Michelle Scavo

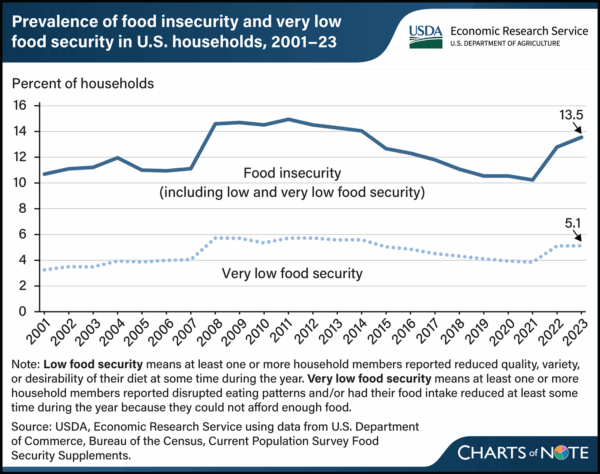

While Turpin’s approach to addressing hunger locally is unique, her experience with food insecurity, sadly, is not. After a decade of decline, food insecurity has only risen since the coronavirus pandemic, jumping by more than 30% between 2021 and 2023. And that was before recent cuts to anti-hunger programs, which threaten to make the problem worse. The reality is that the issues underpinning food insecurity are complex and will require systemic solutions in the long term. Rural places like Questa, and others across the Mountain West, understand this reality: Outside help is probably a long way off, and real solutions to food insecurity even further. So in the meantime, they’re rolling up their sleeves to ensure their neighbors don’t go hungry.

Over the past few years, the LOR Foundation has provided funding for a stream of locally led efforts, like Turpin’s, aimed at plugging the gaps in rural communities—whether that’s finding ways to distribute food to those who need it most or stretching a dollar (or a pineapple) to make food go just a little bit further. Underlying nearly every one of these efforts lies one idea: resourcefulness. The projects themselves reflect the commitment and ingenuity of the people and communities leading the way.

At its root, food insecurity is an economic problem. Simply put: If you don’t have sufficient income or wealth, it’s harder for you to afford food, especially if prices rise. Food insecurity actually dropped by more than 30% between 2011 and 2021 because food prices remained relatively low and stable, while economic growth propelled incomes. But between 2020 and 2024, food prices swelled 23.6%, straining the budgets of many families. In 2023, families living below the federal poverty line experienced food insecurity at a rate nearly three times the national average, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“The entire reason why food insecurity rates rose in 2022 and in 2023 was purely because of inflation,” says Craig Gundersen, an economics professor at Baylor University and food insecurity expert.

Food insecurity fell between 2011 and 2021, but since the coronavirus pandemic it has jumped by more than 30%.

For many rural food banks, seeing the uptick in real life has been startling. Before the pandemic, Shared Table in Taos, New Mexico would see 200 households on a given distribution day. Now, the food pantry, which is run by El Pueblito United Methodist Church, is helping more than 500 families. The largest ever cuts to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) passed in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act risk sending the number even higher. To meet the demand, Shared Table has turned to collaboration, infrastructure development, and local philanthropy. After the Taos Community Foundation paid for two outdoor walk-in freezers, a grant from LOR helped Shared Table build a pathway and renovate the church’s kitchen—all of which helped make the space more efficient for volunteers and staff, allowing them to send more food out the door each distribution day. Today, Shared Table gives out roughly 10,000 pounds of food every two weeks.

But Shared Table itself is contending with the consequences of rising food prices and growing demand. Recent federal cuts have shrunk the meat and produce that food banks receive, and moving forward, Shared Table’s director, Cheri Lyon, worries that the food pantry will not have the resources it needs to meet demand.

“We’re a supplement,” Lyon says. “None of the food pantries are enough to feed a family for a month. That’s not the design of a food pantry.”

Fremont County, in central Wyoming, is nearly the size of New Hampshire. Only a single emergency overnight shelter serves the area: the Warming Hut on the Wind River Indian Reservation. Run by Wind River Family & Community Health Care, the Warming Hut provides one of the few places where residents experiencing homelessness can escape frigid, dangerous winter nights. Many of the people visiting the Warming Hut, though, don’t have consistent transportation, so the food banks and other meal programs in Lander and Riverton (23 and two miles away, respectively) aren’t easy options.

“We just knew [we wanted] to make sure they always had food,” says Kelly Arthur, the Warming Hut’s shelter supervisor. To make that happen, Arthur and her staff reached out to LOR for a $10,000 grant to launch a food distribution program at the Warming Hut. In January 2025, the shelter began distributing oatmeal, breakfast sandwiches, fruit, and other food. The Warming Hut has also worked with Good Portions Mobile Soup Kitchen, another local project kickstarted with funding from LOR, to provide clients with more consistent warm meals. By July, the Warming Hut program had distributed more than 3,000 meals.

At Shared Table, a similar effort is underway to get food to those who need it most. In addition to its distribution days, the food bank runs a delivery program, transporting groceries to about 100 families who are unable to access food banks, soup kitchens, or other resources each month. Many recipients are people with disabilities, a demographic at greater risk for food insecurity, and others who don’t have sustainable transportation. Every month, volunteers see people who ride the bus, hitchhike, or even walk, arriving at the distribution site pushing wheelbarrows and wagons to carry their food home, Lyon says. To help alleviate the burden for working families and reach more people, Shared Table allows visitors to pick up food for others, a contrast from other food banks. Family members, neighbors, and friends can all visit Shared Table and collect food for those who need it. It’s a model built on trust, compassion, and a desire to remove the obstacles that many rural residents must navigate.

Top Left: Cheri Lyon, Shared Table's director, worries the food pantry will not have the resources it needs to meet growing demand.

Top Center: A food box for Taos families prepared by volunteers with Shared Table.

Top Right: A volunteer with Shared Table loads a car for the food bank's delivery program.

Bottom Left: A grant from LOR helped Taos' Shared Table build a pathway to its walk-in freezers so volunteers could move more food.

Bottom Right: Volunteers with Shared Table prepare food boxes under the guidance of pastor Cheri Lyon.

Photos by Ryan Michelle Scavo

Amanda Small has been brainstorming ways to feed more families. The director of Lander Care & Share Food Bank, Small grew up ranching and previously served as an extension educator on the Wind River Indian Reservation, two experiences that have informed her time leading the nonprofit. Her latest initiative: a food repackaging program that launched in October with a grant from LOR.

Local food banks like Lander Care & Share face the same reality as other grocery shoppers: buying in bulk is cheaper. Yet, many rural food banks struggle to buy bulk because the food is harder to distribute; most families can’t easily use or store eight whole chickens packaged together—or 15 pineapples. Small realized that with the right tools, Lander Care & Share could do what other food banks weren’t: buy in bulk and break the food down into family-sized portions. All she needed was $5,000 from LOR for a supply of vacuum seal bags that allowed her to repackage the portions and stretch Lander Care & Share’s buying power to feed more families.

Small and Lander Care & Share are stretching their dollars in another way, too, by preserving food that would otherwise go to waste. When local food banks receive donated produce, much of it is close to or already expiring. The items the food bank can’t distribute in time, or that families don’t know how to use, go to waste. Working with the nearby Meadowlark Market & Kitchen, Lander Care & Share has been able to take expiring food and transform it into ready-made and longer-lasting meals using the kitchen’s food preservation equipment, which was funded by LOR. For example, when Lander Care & Share received a shipment of butternut squash near the end of its life, Meadowlark turned it into soup that was portioned out for families visiting the food bank. “We’re just trying to find creative ways that we can do food,” Small says.

If I give you 30 pounds of grapes, what are you going to do

with it if you don’t know how to preserve it?

In Questa, Turpin, the owner of Rosie’s Smokehouse, turned to her own experience and rural ingenuity, too. Growing up in Questa, Turpin’s grandparents canned whatever they could, a process she helped with but didn’t pick up until her mom later taught her. After learning to can, she quickly became obsessed. When Turpin saw the food pantry box with the pineapples two years ago, she knew exactly what to do. And her vision grew. Now, with an $8,000 grant from LOR, Turpin has launched a series of cooking workshops to help other Questa families who don’t know how to prepare or preserve the foods they receive from the local food pantry. In each class Turpin walks residents step-by-step through the ingredients in their boxes, transforming them into nutritious and delicious meals. If they can’t immediately use some of the items in their boxes, Turpin helps participants preserve them. In her first class in December, families made and canned a Christmas berry jam with frozen blueberries and strawberries. To Turpin, the local solutions to food insecurity are straightforward.

“Teaching people how to be resourceful I think will combat a little bit of food insecurity,” she says. “It’s not going to take care of the entire problem, but I think if we can teach how to start somewhere, let’s just start somewhere.”

Reach out to connect on important matters for your community or your organization.

Born and raised in Taos, Sonya approaches her work with a sharp eye for the values and cultural traditions that make her home unique. She understands that a resilient rural community must provide opportunity for all to prosper, and in… Meet Sonya

Stories

Mapping Taos’ Cultural Assets to Protect the Past and Guide the FutureAmid booming growth, a Taos County initiative charts a path toward sustainable development and community preservation. Read more

Stories

Artisanal Popsicles Help Fundraise for Cortez NonprofitsBuilding on their early success, one Cortez group is creating unique treats that support both the community and local growers. Read more

Stories

An Anthology and Writers Group Elevate Cortez AuthorsThe Four Corners region is home to many talented writers. A new book and nonprofit are giving them a platform. Read more

Stories

Producer Responsibility Program Will Increase Recycling Access in Rural Colorado CommunitiesBy Ilana Newman, The Daily Yonder Read more

If you have an idea for improving quality of life in Cortez or Monte Vista, Colorado; Lander, Wyoming; Libby, Montana; Questa or Taos, New Mexico; or Weiser, Idaho, use this form to start a conversation with us.

"*" indicates required fields