Stories

How New Technologies Save Farmers and Ranchers Time, Water, and MoneyEvery minute counts on a farm or ranch. These innovations are helping agricultural producers across the Mountain West get some of that time back. Read more

Vicente Fernandez lives near the mouth of Taos Canyon, just a stone’s throw from the house where he and his 15 brothers and sisters were born.

The kids grew up raising wheat and corn, and slaughtering sheep and pigs to feed their big family. To survive, they relied almost entirely on a small creek — the Rio Fernando — that starts a few miles up the canyon. The river irrigated crops, and provided drinking water to the family and livestock.

Today, water from the Rio Fernando still irrigates the farms, gardens and orchards just east of Taos. Vicente is in charge of allocating water from the ditch to his friends, family and neighbors. He is also in charge of the small drinking water system that serves about 200 people in his neighborhood. Water is the thread that ties the community together. And today there is a real fear that the thread could break. “If we lose that river, if we lose that water, we die as a people,” Vicente says bluntly.

Since 2014, the LOR Foundation has supported Taos County residents like Vicente in a broad effort to protect the water that makes life possible in the arid West. Around Taos, the foundation has provided grants to ramp up forest restoration efforts based on the best available science. It’s provided funding to study the potential to build a forestry economy that provides good jobs and ecological benefits. And it’s helped bring together local organizations that haven’t always worked together or even gotten along in order to be more effective in safeguarding precious water sources.

“If we lose that river, if we lose that water, we die as a people.”

This summer has been one of the hottest and driest on record. The parched pastures and frequent plumes of wildfire smoke have been visceral reminders that life in the high desert is changing. Fire has also always been a part of life in Taos. Vicente remembers a blaze burning up the canyon while he and his brothers were kids fishing in the creek below. He can still see the fire scar — now an aspen grove — from his driveway.

But these days, wildfires are raging with unprecedented intensity. Vicente says dry spells are more common. It’s getting hotter earlier in the year, and it is staying hotter later. The forests are now thick with vegetation after more than 100 years of stomping out natural wildfires that used to periodically clear out overgrowth and actually improve forest health.

Combined, these conditions could spell disaster for the watershed. It’s not unusual for the Rio Fernando to stop flowing completely in June, and there are serious concerns that a massive fire up that canyon could be the river’s death knell, reducing the entire forest to a moonscape, leading to devastating erosion and mudflows. “A fire like that would probably destroy our way of life,” Vicente says.

In the last decade, the impacts of intense wildfires in the Southwest have been terrifyingly in-your-face. In 2011, the Las Conchas Fire (just 60 miles southwest of Taos) torched more than 100 square miles in three days. Driven by furious winds across a tinder-dry forest, the fire was burning at a rate of an-acre-per-second. The inferno went on to consume almost 250 square miles before it was finally contained more than a month later.

It wasn’t just the size of the Las Conchas fire that shocking. It was the intensity with which it burned. The fire was much hotter and moved much faster than the naturally occurring fires that the forest evolved to tolerate. Fires like the Los Conchas don’t provide ecological balance. They obliterate it.

The Spring Creek Fire in south central Colorado burned 141 homes and more than 100,000 acres in the summer of 2018. Efforts just across the state line in Taos County, New Mexico hope to reduce the risk of this kind of fire while nurturing a restoration economy built on good paying jobs that help prevent environmental catastrophes.

Worse, the scorched hillsides became coursing sheets of mud and ash when bare soil was hammered with torrential summer rains. Rivers of black sludge poured into the Rio Grande — the primary water source for a million people that live as far downstream as Mexico. Drinking water providers were forced to stop taking water from the Rio Grande until the sludge-choked river cleared.

The Las Conchas fire was a wake up call. Residents across New Mexico realized this kind of fire was going to be more common and more devastating. Something had to be done. So in 2014, the Nature Conservancy’s New Mexico field office founded the Rio Grande Water Fund as a way to tackle a seemingly impossible problem. The fund sought to unite individuals, businesses, nonprofits and government agencies around the goal of drastically increasing the rate of forest treatments in the Rio Grande Basin.

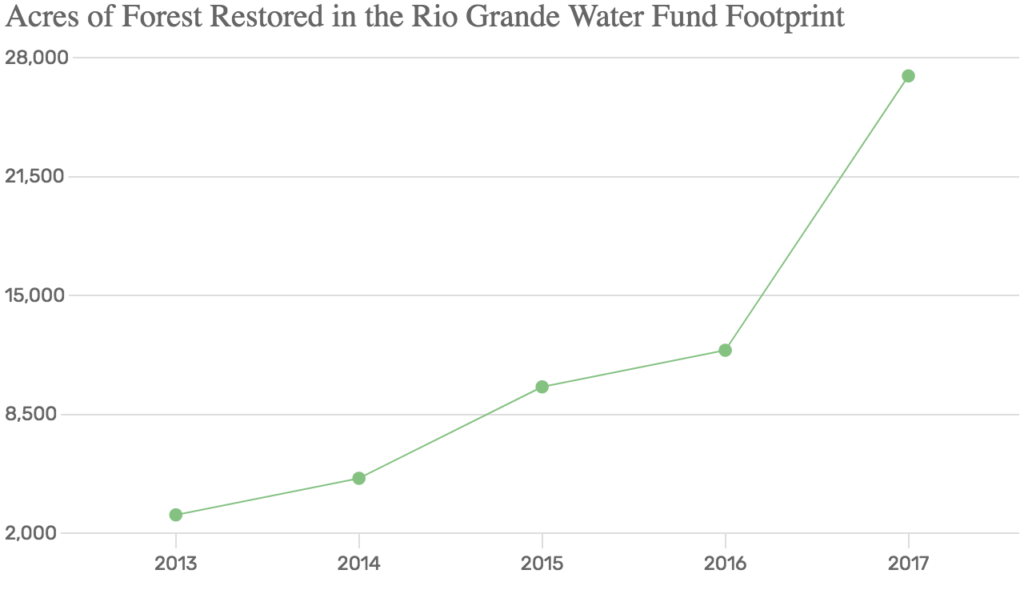

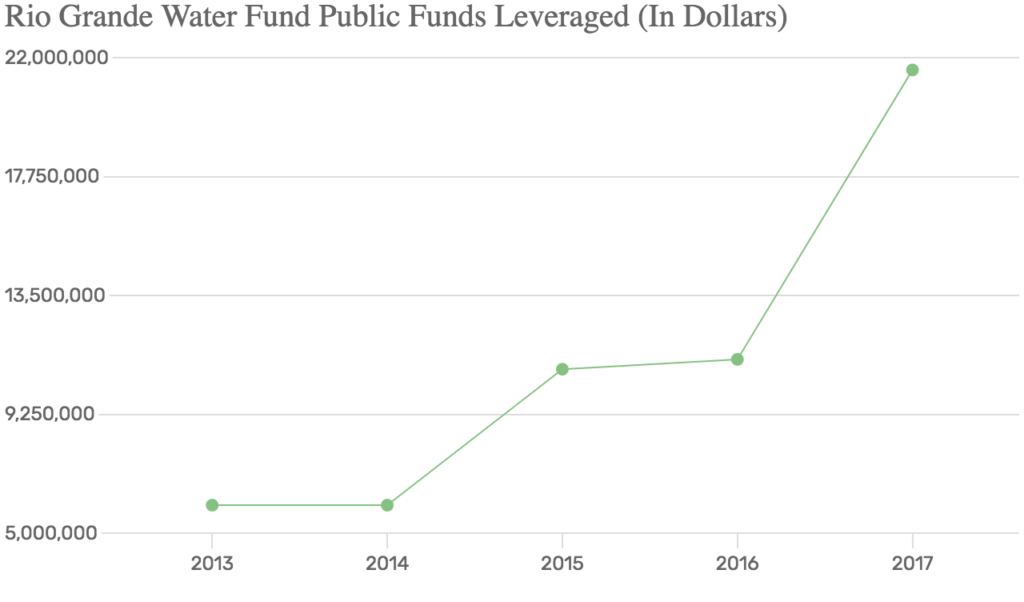

In just five years, the Rio Grande Water Fund has helped ramp up the pace of forest treatments across New Mexico.

Thanks to an initial grant from the LOR Foundation, the fund recruited dozens of partners who agreed to contribute funding and/or technical expertise to start coordinating bigger and broader restoration work, especially in the river’s northern headwaters. It also put money toward state-of-the-art research to identify areas in the basin where a catastrophic fire would have the worst impacts on watersheds.

Among the areas at highest risk was the west flank of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in Taos County.

The Taos Valley Watershed Coalition formed in 2015 to connect forest restoration work up and down the west flank of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in Taos County. The coalition relied on scientific data to identify areas that were at the greatest threat from intense fire and dangerous post-fire runoff.

Mark Schuetz is in his early 50s, but he’s got the energy of a 17-year-old. Lean and gregarious, Mark was born and raised in northern New Mexico, and now runs a small land restoration business that does everything from thinning trees to cutting hay. Mark is part of the Taos County CORE Team,” which includes local wildfire experts as well as interested community members. The group was formed years ago as a way to get more involvement, input and support from local residents in restoration and fire protection efforts. For the Rio Grande Water Fund, the CORE Team was a perfect venue to make its pitch.

When a representative of the Rio Grande Water Fund showed up to one of these meetings asking the group to submit a proposal to fund restoration work, Schuetz saw it as a game changer. “They were thinking big,” Schuetz says.

In response, the group created the Taos Valley Watershed Coalition — an organized collaborative aimed at restoring forests within a 280,000 zone around Taos. Later that year, the group was awarded $225,000 from the fund, split evenly between Taos Pueblo, the Forest Service, and El Salto Del Agua Land Association — a private corporation owned by the heirs of the Spanish pioneers who first settled in the area 300 years ago. On the ground, those funds would create a fire buffer that crossed federal, tribal and private boundaries.

Mark says the Fund has inspired people to work together in ways that weren’t possible a decade ago, and the direct funding has been great. “It has changed the perspective that it’s somebody else’s responsibility,” Mark says. “Now it’s the people here doing it for themselves. And we’re all in it together.”

Between 2013 and 2017, the Rio Grande Water Fund helped increase the amount of public funding going toward restoration work by more than three and a half times.

The Rio Grande Water Fund has also commissioned studies specific to Taos to quantify the economic impact of a devastating fire, as well as, potentially profitable uses for the massive amounts of small timber that will be cut down as part of restoration work.

The initial funding and blossoming partnerships has led to even more money for restoration work. Taos Valley Watershed Coalition partners have successfully brought in another $1 million in grants, largely because of group’s momentum and on-the-ground results. For Schuetz, this means he’s able to hire more people and treat more acres, boosting the local economy for small businesses like his while taking steps to make the community safer.

Irene Neimeyer and her husband moved from St. Louis to Taos in 2008 to realize their dream of leaving the midwest for the mountains of New Mexico. They bought a house a few miles east of town, in a subdivision up a narrow wooded canyon. “We really loved the aspens and pines, the grasses and the flowers, and all the greenness that comes with living in a mountain valley.”

The couple learned to deal with the less glamorous parts of mountain living, like getting around through blizzards and over icy roads. They also realized that things could look very different if a major wildfire ever tore through their canyon. “We could be living in a charred crater instead of a beautiful valley,” Irene says.

Irene began attending community meetings around the county to learn how she and her neighbors could protect themselves and their properties. What she found was a network of motivated public servants — including agency officials from the Taos Valley Watershed Coalition who were doing more public outreach to build support for forest restoration.

A county employee, hired specifically to go neighborhood to neighborhood, helped residents recognize and address the risk of wildfire and get organized as a Firewise Community—a national program that encourages activities like community cleanup days to clear out brush and other quick-burning fuels. The county employee’s support also included a professional risk assessment and fire simulations that Irene describes as “eye opening” in demonstrating the havoc a dangerous fire in their canyon would wreak.

So Irene and many of her neighbors got to work. Her husband cleared about 100 trees from their four-acre property to create a defensible buffer and make the remaining trees around their house healthier. A Boy Scout troop was hired to rake pine needles and duff away from homes in the neighborhood. Expert speakers were brought in to talk to the homeowners association to drive home the importance of taking preventative steps and making a plan if a fire ever bore down on their subdivision.

For Irene, getting proactive about wildfire protection made her more informed and a lot less helpless. “Do I feel 110 percent safe? No. But I feel a lot safer,” Irene says.

To build on the growing public awareness, LOR brought in experts to help Taos County officials develop public outreach tools to explain the new reality of living with wildfire in the Southwest. More knowledge and more connections between fire officials and community members have opened the door to managing fires in ways that were inconceivable a decade ago.

In 2016, lightning started a wildfire on the national forest just south of Taos. In the past, any smoke on that hillside would have prompted demands from the community that the fire be stomped out immediately. But federal officials called a community meeting and explained that this fire was relatively mellow thanks to some recent rains. If managed well, officials said the fire could clear out a lot of the overgrowth that would fuel a dangerous blaze in drier conditions. The community showed unprecedented trust when it agreed to let the fire go. When it was finally snuffed out, the fire brought about 550 acres back into ecological balance at minimal cost.

Like a lot of young people in Taos, Paula Archuleta got a job washing dishes at a restaurant after high school. But she didn’t like being stuck inside, and she had no interest in an office gig, so she joined a tree thinning crew. At 18, she was trained to use a chainsaw like a pro, and she gained experience thinning forests near Taos. Five years later, she’s making a living doing what she loves, and she feels like her work is improving things in her community.

“I like being able to look at a job when we’re finished and know that it’s helping people,” Paula says.

Part of the reason Paula hasn’t had to go back to dishwashing is the increasing pace of restoration work in Taos County. As thinning contracts get more plentiful, the goal is to give more young people like Paula the chance to work in the woods and make a career out of it.

There are signs that it’s already working. Statewide, the total number of forestry jobs rose 5 percent between 2014 and 2017. But rebuilding the industry comes with plenty of challenges. Almost all of the trees being cut down are too small to turn into lumber. And there’s not yet enough work to keep contractors busy full time, though that’s likely to change soon.

I like being able to look at a job when we’re finished and know that it’s helping people.

There are several projects in the planning stage and hundreds of acres of new work in the pipeline. The Taos Valley Watershed Coalition is now focusing more attention on building up the local forestry workforce and create opportunities for young people like Paula. The Rio Grande Water Fund has also teamed up with Taos-based Rocky Mountain Youth Corps to develop a pipeline to get young adults positions on local wildfire crews. Efforts are also coming together to give more professional training to locals who already gather firewood (but don’t necessarily have forest thinning experience) as a way to expand the local workforce.

From his back porch near Taos Canyon, Vicente Fernandez acknowledges that locals have long been wary of government and of so-called environmentalists. But he says attitudes are changing, partly because of new relationships born out of the need to act.

In 2017, building on the success of the Taos Valley Watershed Coalition, LOR provided a grant to an unlikely group to develop a top-to-bottom approach to protecting the Rio Fernando watershed — the primary water supply for the heart of Taos. The group includes local government officials, acequia advocates like Vicente, conservation organizations like the Taos Land Trust, a representative of the Rio Grande Water Fund and environmental groups like Amigos Bravos. The group is developing a long-term action strategy that includes everything from improving water quality and stream health at the top of the watershed, to making irrigation works more efficient, and developing more parks and public access along the river in town.

A project like this is so important for the environment, for our agricultural traditions and for the economy. We all see something’s wrong. And we want to improve it.

Vicente says the unlikely alliance of traditional farmers, government officials and environmentalists has the potential to make a lasting difference. “We started to talk, and we’ve gotten to be friends. And we’re getting a lot more done,” Fernandez says. “A project like this is so important for the environment, for our agricultural traditions and for the economy. We all see something’s wrong. And we want to improve it.”

Stories

How New Technologies Save Farmers and Ranchers Time, Water, and MoneyEvery minute counts on a farm or ranch. These innovations are helping agricultural producers across the Mountain West get some of that time back. Read more

Stories

How Western Sheep Producers Are Using Waste Wool to Save WaterSheep ranches across the West are finding both financial and agricultural value in what was previously considered worthless wool. Read more

Stories

How Fenceless Ranching is Transforming Land and Water in the WestColorado's Badger Creek Ranch is using electric collars to guide cattle to water—and away from sensitive areas. Read more

Stories

A Community Cistern Restores Water for Students at Battle Rock Charter SchoolAfter contamination left kids unable to drink or wash their hands at the Cortez school, one teacher rallied to keep the water flowing. Read more

If you have an idea for improving quality of life in Cortez or Monte Vista, Colorado; Lander, Wyoming; Libby, Montana; Questa or Taos, New Mexico; or Weiser, Idaho, use this form to start a conversation with us.

"*" indicates required fields